By John Beydler

Copyright 2020 All rights reserved

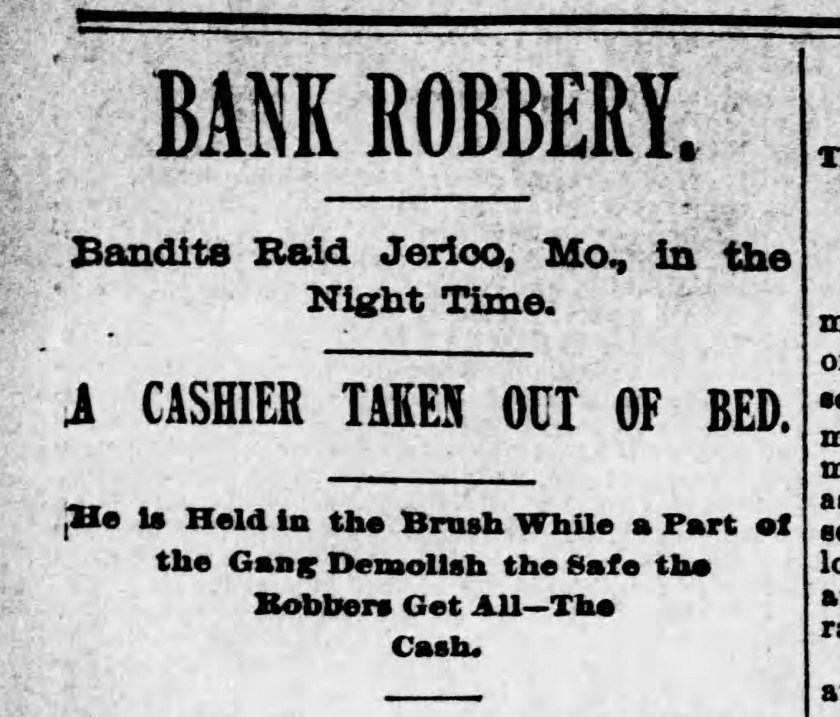

A crooked cashier and a staged robbery in the wee morning hours of June 28, 1893 brought down Jerico’s first bank, touching off a local financial crisis and a week of high drama featuring a near-lynching.

The collapse of the Hartley Bank of Jerico “makes things bad for the Jerico people,” said the Dade County Advocate in Greenfield in its July 6 issue.

“The bank was a popular one and many of the merchants and businessmen kept their money there. Many stockmen, too, who (are) buying for feeding for the fall markets had their deposits in this bank, and the wreck has been a paralyzer of business,” the paper said.

An integral part of Jerico’s economic life since it opened in March 1884, one year after the village incorporated, the bank was named for J. E. Hartley, the Stockton banker who organized it, according to Goodspeed Publishing Co.’s 1889 “History of Hickory, Cedar, Polk, Dade, and Barton Counties, Missouri.”

The bank, name aside, had a distinctly Jerico tone from the beginning.

The first president was A. M. Pyle, described in the newspapers as a Jerico stockman who “is among the wealthiest men in this area.” The vice president was Dr. Joseph P. Brasher, among Jerico’s best known and most popular citizens.

In 1886, Mr. Hartley sold his stock in the Jerico bank as he opened a new one in Mount Vernon. John Porter, the cashier at the Jerico bank, moved to Mt. Vernon as well and was replaced by Dr. Brasher’s younger brother, Byron L. Brasher, a farmer west of Jerico.

By 1891, when the Cedar County Board of Equalization ran a legal ad listing all the stockholders in all the county’s banks, five members of the Brasher family held 61 of the Hartley bank’s 110 shares. Dr. Brasher held 21 shares, brother Byron held 10, brother F. A. held ten and and two additional Brashers held 10 each.

Other, smaller shareholders amounted to a mini-who’s who of Jerico. They included A.M. Pyle, the wealthy stockman; J. B. Carrico Sr., who had been the first white settler in the Jerico area; D. G. Stratton, Jerico’s founder; Morris W. Mitchell, a former Cedar County sheriff who was also Dr. Brasher’s father-in-law; as well as several merchants.

The bank’s directors “are among our best and most influential citizens,” the Stockton Journal said in an 1888 story noting the bank’s latest report showed it to be in excellent condition. Its balance sheet showed assets of $37,586 on April 30, 1888 ($1.1 million in 2020 dollars). Of cashier Byron L. Brasher, then 35 years old, the paper said, “he is fully qualified for his duties… and honored for his honesty and uprightness.”

Then came June 28, 1893.

Cries of fire! fire at the bank! awakened sleeping villagers sometime after 3 a.m. People answering the alarm found Byron Brasher already on the scene and helped hm extinguish the blaze, which burned a hole in the floor and damaged a counter.

The cashier told his fellow townsmen two armed men came to his house shortly after midnight and forced him to go to the bank, were two more bandits awaited. After various twists and turns, the bandits, frustrated by the time lock on the safe, took $100 left out to cover an anticipated early morning transaction and set fire to the bank before fleeing, Mr. Brasher said.

That’s the story widely reported all through the state beginning the next day, with reports of the loss running as high as $10,000 ($281,000 in 2020 dollars).

But in Jerico, as posses fanned out in search of the bandits and the cashier’s story winged its way toward front pages, residents puzzling over the day’s events were soon casting suspicious eyes at Byron Brasher.

The Greenfield Vedette picks up the story:

“The time lock did not open at the usual hour and the owners and depositors of the bank decided to force an entrance. The steel hinges of the outside door were cut but as no keys were at hand, the apartment containing the money could not be opened. A combination of circumstances set the depositors to thinking and the result was that cashier Brasher was arrested, awaiting further developments.”

Taken into custody later on the day of the fire, Mr. Brasher was taken to Stockton Thursday, where friends posted $2,000 bond and he was given his freedom until a court appearance set for Friday, July 7.

But, the Vedette reported, “his bondsmen, influenced by the general excitement, gave him up to the authorities” on Saturday, July 1.

“When the officers went to arrest him the second time, he drew a revolver and, threatening to kill the first man who interfered with him, made his escape to the woods.

“On Saturday night the citizens became excited beyond reason,” the paper continued. “Many of the businessmen of Jerico, formerly warm friends of Mr. Brasher, were the bitterest to denounce him, and if he could have been found it is very probable that he would have been lynched.”

The Dade County Advocate said, “Depositors are wild with suspense and excitement and strong talk of violence to the cashier has been indulged in, so much so the cashier refuses to give himself into the hands of the Jerico authorities, but we understand is willing to surrender to the authorities of Stockton.”

Cooler heads prevailed, perhaps assisted by a spreading general belief that depositors’ losses would be made good.

“A.M. Pyle, President of the troubled bank, is one of the wealthiest men in Southwest Missouri and it is generally understood that if there is a shortage, the depositors will be made whole, the Vedette said July 6.

It wasn’t until Monday, July 3, five days after the fire, that the bank’s vault was finally forced open and an assessment of the losses could begin. The July 7 Cedar County Republican said $1,400 was found, “this being considered a very small amount of the funds that should have been on hand according to the semi-annual statement given on the last day of April.”

The Republican reported in the same story that cashier Byron Brasher, now free on a larger bond, had been Stockton July 4 and “procured of druggist Clayton Rogers a large quantity of morphine, by telling Mr. Rogers that he was getting it for his brother, Dr. Brasher. Report says that he took a large dose of it” later in the day and “was unconscious.”

He did not appear for the July 7 preliminary hearing. (The papers never said what he was charged with at this point.)

Depositors acted swiftly to secure their claims. At a meeting on July 21, C. S. Brown, a leading real estate agent, was appointed assignee to handle claims and a three-person advisory committee named to assist him. (One committee member was Crafton J. Beydler, my great-grandfather.)

“Suits were immediately brought against the officers of the bank and attachment served on the entire real property of A. M. Pyle, president; Joseph Carrico, Sr., vice president; B. L. Brasher, cashier; also Dr. J. P. Brasher and Frank Brasher, directors” reported the Jerico Advocate, a short-lived paper that competed with the Optic for part of 1893.

“The general impression is that with the means on hand the loss of the depositors will be small, the Advocate said.

On Aug. 31, the Nevada Noticer, quoting the Optic, said approved claims amounted to $29,495. The paper said claimants of about $1,000 were expected to appeal Mr. Brown’s rulings against them. In addition, a special referee had yet to rule on claims by Mr. Brown and his business partner, C. E. Whitsitt.

The loss then, would have been at least $30,000, or more than $850,000 in 2020 dollars

The Springfield Democrat reported March 10, 1894, that creditors had been paid “about 20 per cent of their claims” and that “the property and assets of the institution will not pay the debts.”

The story said “those pieces of property turned over by the Brashers to make the loss good” were being advertised for sale.

The Brashers had a great deal of land, or at least they did in 1879, when a Cedar County plat map showed various members of the family (not all involved with the bank) holding more than 1,300 acres west and north of Jerico.

I’ve seen nothing more on whether losses were all made good, but they may well have been. Certainly Dr. Brasher continued as a well-respected member of the community, as witnessed by the huge crowd of people who turned out for his funeral when he died unexpectedly at age 49 in 1899.

People, too, seem to have lost their appetite to do harm to Byron Brasher. He was finally indicted in October 1893, but only on three counts of taking deposits into the bank when he knew it was failing. The case dragged on and in March of 1895, it was transferred to Barton County on a change of venue.

On Aug. 30, 1895 the Cedar County Republican said Sheriff R. S. Holman was delivering subpoenas to 45 people likely to be called as witnesses in the Brasher trial. According to Barton County court records, the charges of taking deposits into bank he knew to be failing were dismissed late in 1895, to be replaced by a charge of larceny. A jury found him not guilty in January of 1896.

From at least 1903, Mr. Brasher lived in Joplin, where he worked as a miner, laborer and mover, among other jobs, according to various Joplin city directories. He died March 30, 1928.

Jerico was quick to pick up the pieces. Four months after Hartley’s closed, Joseph Morris, its largest non-Brasher stockholder, combined with C E. Whitsitt, a leading businessman, to announce the formation of the Morris Bank of Jerico, with capital stock of $5,000 ($143,000 in 2020 dollars.

The Morris bank never opened.

Instead, Mr. Whitsitt joined with Peter Lloyd of Mount Ida, Iowa, to form the P. Lloyd Banking Co. of Jerico, which opened in November 1893 with capital stock of $20,000 ($575,000 in 2020 dollars).

Posted March 31, 2020

Revised Sept. 10, 2020

Reviewing history Jerico had a lot of crooks.

LikeLike