Jerico’s banks and their lifespans

- The Hartley Bank of Jerico: March 1884 – August 1893

- Morris Banking Co: October, 1893 – November, 1893

- The P. Floyd Banking Co. November 1893 – Sept. 1, 1902

- The Bank of Jerico: Oct. 18, 1901- July 6, 1916

- Farmers State Bank of Jerico Springs: March 5, 1909 – Feb. 8, 1911

- Farmers Bank of Jerico: May, 20, 1912 – Dec. 26, 1923

- Peoples Bank of Jerico: Feb. 27, 1919 – March 16, 1929

- State Bank of Jerico: Sept. 29, 1924 — March 11, 1927

—————————————————————

By John Beydler

Jerico Springs and its banks rose and fell together.

The first, the Hartley Bank of Jerico, opened in March, 1884, as the village grew rapidly one year after it incorporated. The 1890 census reported a population of 486.

The last, the Peoples Bank of Jerico, closed March 16, 1929, its officers facing criminal charges and the town decaying even before the Great Depression began in earnest. The 1930 Census put the population at 247, barely half of 1890’s.

Besides the usual services, the banks that existed along the way repeatedly provided Jerico with moments of high drama that drew headlines throughout the state and beyond.

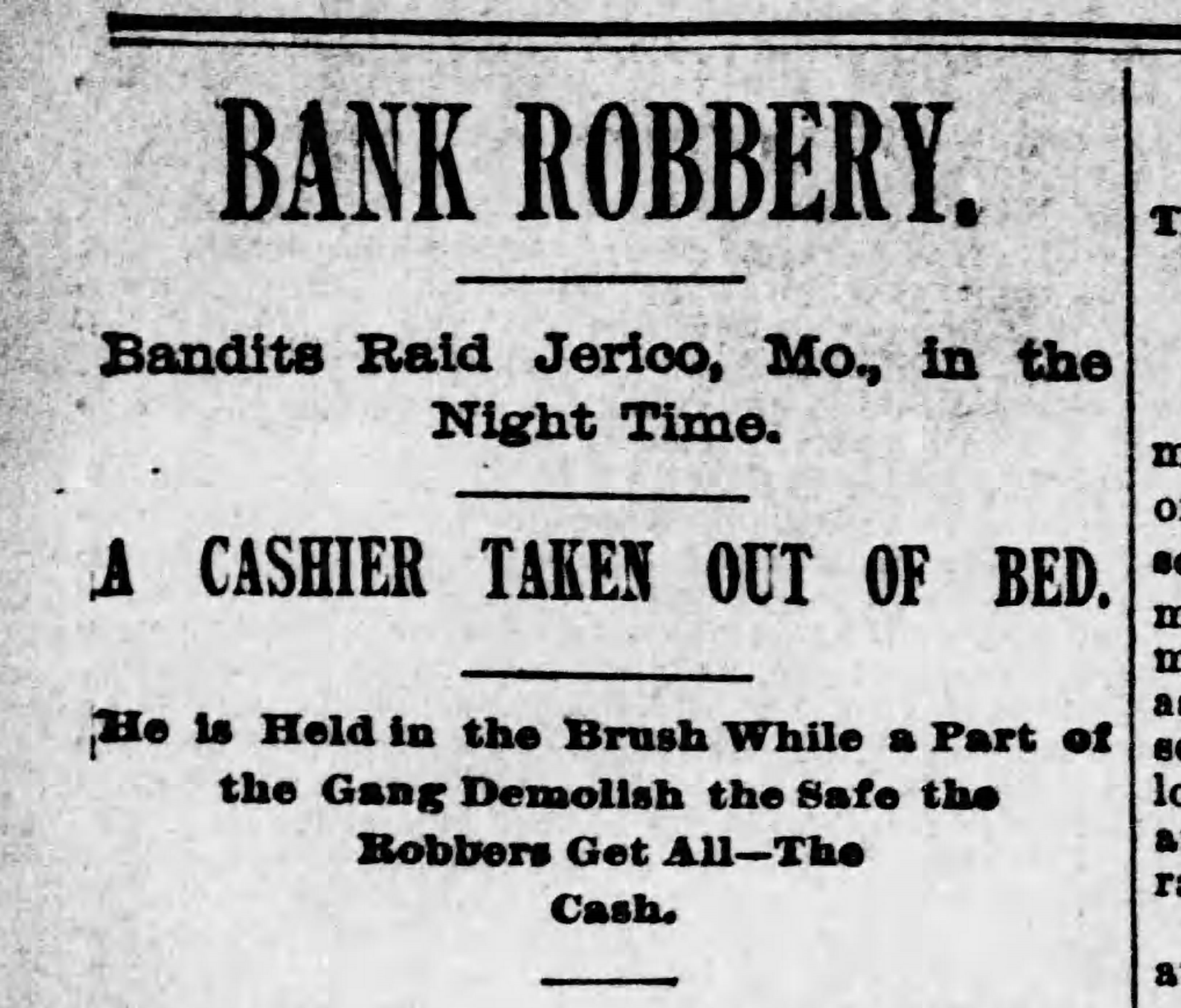

There was the “robbery” and manhunt that preceded the collapse of the town’s first bank in 1893.

In 1916, in a scene fit for a Frank Capra movie, a tense public meeting in the park turned into a community-unifying moment that averted a banking disaster.

On Christmas Day, 1923, a bank’s failure was announced by the suicide of its cashier, who was also Jerico’s mayor.

The banks also were central to what are most likely the only two Missouri Supreme Court cases to arise out of Jerico.

Despite all that and the steady downward trend in population, the ever-evolving banks drew a steady stream of investors whose money was a demonstration of their basic faith in the future of Jerico. Eight banks were organized in the 45 years spanning 1884 to 1929. For about a third of that time, two were in business simultaneously, which suggests the town possessed both a competitive spirit and a sense of optimism.

Jerico’s original economic engine was the healing springs that drew people seeking to cure or ease the pain of various ailments. The first two houses on the town site served as hotels until others were erected,

according to Goodspeed’s “History of Hickory, Cedar, Polk, Dade, and Barton Counties, Missouri” , published in 1889.

That source says the United States Hotel was built in 1882, the year before Jerico incorporated. The Neumann House was built in 1883. Bath houses also sprung up and civic leaders always saw travelers to the springs as a possible source of economic growth. Others saw potential, too.

Railway World magazine, in a 1904 story about a proposed railroad that would pass through Jerico, said one of the benefits would be to give “the health resort” transportation facilities. Alas, the proposed road was never built.

In the event, it was the needs of the farmers and stockmen in the surrounding countryside rather than health-seekers that drove Jerico’s growth.

In a time of dirt roads, few bridges and animal-powered transportation, Jerico’s first merchants and tradesmen found success by bringing a gamut of goods and services within easy reach of a wide stretch of farm country. Roughly equidistant from El Dorado Springs, Stockton, Lockwood and Lamar, the new village found room to grow quickly. The Missouri State Gazetter for 1893-94 listed nearly 100 businesses and services available in the 10-year-old town.

An opportunity to provide banking services would have been obvious. Experienced outside entrepreneurs spotted it and helped organize Jerico’s first two banks, with Jerico people putting up some or most of the money.

Later banks were financed entirely by Jerico’s merchants, farmers and professionals, who also served as bank officers and directors.

Jerico’s banks weren’t particularly large. They held fewer assets than banks in neighboring Lockwood, Greenfield, Stockton and El Dorado, according to various biannual reports by the state banking commission.

At the end of 1916, for example, the Farmers Bank of Jerico had $103,000 in assets, less than half those at any of the neighboring towns’ banks and less than a third of El Dorado’s.

Still, in a time when banking was very lightly regulated and residents of just about every town organized a bank or two, Jerico’s were larger than many around Missouri. Banks with assets of $30,000 and less were common.

At peak in 1919, Jerico’s banks – there were two that year – held combined assets of $277,390.25, or about $4.04 million in 2019 dollars, according to usinflationcalculator.com.

So Jerico’s banks could readily meet many of village residents’ financial needs. How exactly they used the money is impossible to know, given the bare-bones nature of their annual reports — loan portfolios were divided no further than “loans” and “real estate loans.”

Real estate loans were consistently a very small percentage of total loan portfolios. It seems likely, then, that commercial loans, personal loans and operating loans to farmers formed the bulk of business.

In any case, Jerico’s banks kept their money at work in the community; outstanding loans were often nearly equal to or even greater than deposits, according to the annual reports. The banks rarely held stocks or long-term certificates of deposit in other institutions.

Most had correspondent relationships with a bank in a neighboring town and sometimes with one in Kansas City or St. Louis as well, giving them access to a broader financial network.

THE HARTLEY BANK

The first bank for which I found documentation was the Hartley Bank Of Jerico, which opened in March 1884 with $11,000 in capital, according to Goodspeed’s “History ,” which says the bank was “organized” by J. E. Hartley, who had opened the Stockton Exchange Bank in 1881.

However much stock Mr. Hartley held and whatever his role in organizing the bank, he was not among the first officers and board members. Those were most likely Jerico people since they bore the surnames of long-resident Jerico-area families. A.M. Pyle was president, J. P. Brasher was vice president, and John D. Porter was cashier. Typically, officers and directors were stockholders, often major ones.

The county history cited above said Mr. Hartley sold his stock in the Jerico bank in 1886, as he launched a new bank in Mount Vernon.

The Hartley Bank in Jerico retained his name. It is listed throughout the 1880s in The Banker’s Almanac and Register, with A.M. Pyle as president and B. L. Brasher as cashier, except for 1887 when the president was J. B. Carrico Jr., a Jerico merchant and son and namesake of an early settler.

The Directory of Missouri for 1887-88 said the Hartley Bank had $20,196 in deposits and $32,237 in assets as of Dec. 31, 1887 ($852,526.13 in 2019 dollars).

The Hartley Bank operated until August 1893, when it closed its doors, according to the Banker’s Magazine and Statistical Register. The magazine gave no reason for the closure but newspapers in Missouri and neighboring states were all over it.

The initial story out of Jerico was that two armed men had gone to the home of cashier B. L. Brasher shortly before midnight June 27, 1893, and forced him to go to the bank, where two more armed men awaited. They eventually fled with the contents of the safe, $5,000-$10,000 according to the June 29 Kansas City Gazette. That was a colossal sum – $5,000 is 1893 is equivalent to about $140,000 in 2019 dollars.

But the next day’s Springfield Democrat said the earlier reports were wrong; that a time lock on the safe had frustrated the robbers, who got only $50 from a change drawer. They had set fire to the bank in frustration before fleeing but Mr. Brasher sounded the alarm and fire was put out with little damage done.

The story soon changed even more dramatically. On July 4,The Democrat reported that Mr. Brasher’s entire story was false, that he had been arrested placed under a $2,000 b0nd and an increase in that amount was being sought. But too late. The Democrat said July 6 that Mr. Brasher had mounted a horse and fled even as the bond was being hiked.

Auditors and accountants were soon going over Hartley’s books, trying to sort out the truth. I don’t know the details, but the bank was soon closed for good. The Democrat said, without attributing its statement, that other stockholders in the bank were expected to make good any losses suffered by depositors.

I do not yet know Mr Brasher’s fate but he was arrested within a couple of weeks. The Garnett, Kan., Journal-Register reported July 14, under a dateline of Nevada on July 12, that Mr. “Brashear” was recovering from an overdose of morphine and that an additional bond of $6,500 was being required of him.

Here’s a link to more information, including contemporary news accounts: The great Jerico Bank Robbery – 1893

THE P. LLOYD BANK

The demise of Hartley’s set off something of a scramble to fill the vacuum. The exact maneuverings are unknowable at this remove, but in October, about six weeks after Hartley’s closed, organizing papers were filed for the Morris Bank of Jerico, with Joseph Morris as president and Charles E. Whitsitt as cashier. Capital was $5,000.

Within weeks, though, in November,1893, the Morris Bank was “succeeded” by the P. Lloyd Bank, according to Banker’s Magazine and Register. P. Lloyd had capital of $20,000 ($560,000 in 2019 dollars).

Among The Lloyd bank’s incorporators were Mr. Whitsitt, cashier of the gone-before-it-opened Morris Bank, and Mr. Carrico, who had been a director and officer in the Hartley bank. Both men were players in Jerico banking for a quarter-century.

The other incorporators were Peter Lloyd, the president, and C. W. Sheppard, the vice president.

Subsequent events suggest Mr. Lloyd, of Ida Grove, Ia., held controlling stock in the bank. Why he chose Jerico – 400 miles from home – as a place for a banking investment is lost to the mists of time. But Mr. Lloyd, a prominent citizen in Ida Grove, obviously liked Jerico, however it came to his attention.

The P. Lloyd Bank had Jerico’s banking business to itself until 1901, when Mr. Lloyd died and a split ensued when the bank board met Aug. 16 to choose a new president.

Richard Jones of Ida Grove was selected, whereupon Mr. Whitsitt, the cashier and a founding incorporator of the bank, resigned. He was replaced by his deputy, Leonard Smith, an Ida Grove man. Mr. Carrico remained as vice president.

Mr. Whitsitt announced his plans in the same issue of the Jerico Springs Optic that carried the story of the changes at P. Lloyd:

“Mr. C. E. Whitsitt authorizes the Optic to say that he is organizing a new bank in Jerico. He has the stock about all subscribed and will be ready for business in the near future. What the capital stock will be will be announced by him later.”

THE BANK OF JERICO

On Oct. 18, 1901 The Bank of Jerico opened after selling $12,000 in capital stock, the Optic reported. J. W. Nebelsick, a furniture dealer/undertaker, was president and Mr. Whitsitt, late of the Lloyd Bank, was cashier.

After barely a month in business, on Nov. 23, 1901, the new bank reported assets of $20,916.40.

The Lloyd Bank reported assets of $83,834.80 on that date. It had deposits of about $54,000, far more than the new bank’s $8,000 and change.

Despite the seemingly dominant position of the Lloyd Bank, it pulled out of Jerico within the year, its investors in search of greener pastures.

The Optic reported in depth on the decision in the Oct. 10, 1902 edition.

The newspaper said that after Mr. Jones took over as president of P. Lloyd, “he found securities for some loans to be unsatisfactory and set about to correct them by demanding additional security. This of course created some little friction among the parties interested but after the matter became thoroughly understood by the borrowers and patrons of the bank Mr. Jones” was shown to be right, “thus showing (his) business sagacity and increasing the confidence of the depositors in the stability of the bank and business began to show a marked improvement.”

But further examination of the business had convinced Mr. Jones the return on capital was insufficient, the Optic reported. “After due consideration (he) concluded to close up their banking business here with a view of finding a more favorable locality.”

The Optic editor was effusive in his praise of Mr. Jones’ conduct in wrapping up the bank’s business affairs. “Notwithstanding the unfavorable crop conditions of last year, (he) succeeded in collecting the outstanding loans with a remarkable degree of success and did it, we are informed, without bringing suit in foreclosure in a single instance, due largely to Mr. Jones’ ability and foresight.

“Mr. Jones is a gentleman in every particular both socially and morally and has made many friends among Jerico’s conservative businessmen and farmers and the P. Lloyd Bank will be missed in our town.

“Mr. Jones departed for his home in Ida Grove, Iowa, Saturday last and the Optic wishes him success wherever he may go.”

Given the praise for Mr. Jones, it’s probably safe to say that neither stockholders nor depositors suffered in the bank’s withdrawal from Jerico.

The closure of the Lloyd Bank left the field clear for the Bank of Jerico, which had no competition for the next seven years.

Its stockholders in 1902 were Joseph Morris (who had been president of the organized but never-opened Morris Bank), T. J. Pyle, Laura Martin, F. K. Crawford, C.E. Whitsitt, J. W. Nebelsick, George Frieze, M. B. Pyle, L. C. Gates, J. W. Tare, Jacob Horn, J. W. Potts and Elizabeth Spencer, according to a bank ad in the Optic.

On Sept. 23, 1908, as its competition-free run neared its end, the Bank of Jerico had $68,132.42 in assets ($1.87 million in 2019 dollars). It had more than $41,000 in deposits and $53,000 loaned out, according to its annual report.

Those assets were about 22 per cent less than the two banks held in total when the P. Lloyd Bank pulled out of town six years earlier. The town’s banking assets had shrunk while the Bank of Jerico held a monopoly.

That may have been a factor, along with whatever personal, commercial and political rivalries were in play, when a group of residents in 1909 launched a persistent effort to challenge the Bank of Jerico.

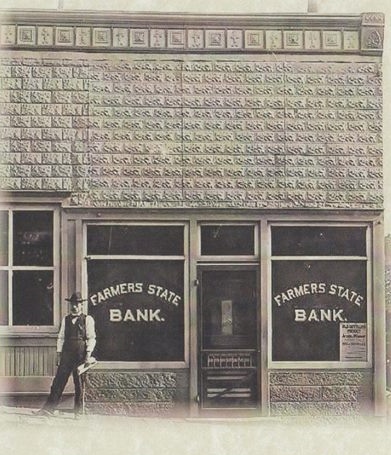

THE FARMERS STATE BANK OF JERICO

Here’s the Optic report as they launched their first try:

“A number of Jerico Springs and vicinity’s citizens met in the law office of attorney Hightower Wednesday afternoon and organized a new bank, the name of which is the Farmers State Bank of Jerico Springs. J. K. Peer was elected president and W. A. Carender, cashier. The board of directors consists of I. L. Arnold, Henry Willmann, W. A. Carender and J. F Brown.

The editor said, “The president of the institution (Mr. Peer) needs no introduction to the readers of the Optic. His home has been in our midst since the town has been here and his business interests have always been in Jerico Springs. Mr. Carender, the cashier, was formerly a member of the firm of Carender and Gates and has made many friends throughout the country.

“The stockholders are all residents of Jerico Springs and community and need no introduction to our readers with, possibly, the exception of Mrs. J. D. Eubanks, sister of Mrs. L. C. Gates. Mrs. Eubanks was an extensive land and cattle owner in Texas and came here recently to reside with Mrs. Gates.”

The Optic listed the stockholders: J. K. Peer, W. A. Carender , Mrs. L.C. Gates, J. H. Arnold, Henry Willmann, William T. Long, Mrs. A. E. Grainger, Mrs. J.D. Eubanks. C. E. Jones, J.F. Brown, I. L. Arnold , W. H. Haubein, Mrs. Carolyn York.

G. W. Freize, a stockman and mule breeder, replaced Mr. Peer as president a year later, according to the annual report.

The new bank apparently stimulated growth generally. By the end of 1910, it had $40,642.28 in assets. The Bank of Jerico grew nearly as much and held assets of $100,412.15. In short, the assets of Jerico’s banks had doubled in little more than a year.

The competition was short-lived. The Bank of Jerico fought off its new rival by buying it on Feb. 8, 1911.

The Optic carried only a brief formal announcement from the banks. Neither the reason for the sale nor the price were reported.

“Public notice is hereby given that the bank of Jerico has purchased the Farmers State Bank of Jerico Springs, the entire holdings of the Farmers State Bank have been transferred to the Bank of Jerico and all customers of the Farmers State Bank will be satisfactorily taken care of by the Bank of Jerico and every courtesy extended them.

Signed: C. E. Whitsitt, cashier Bank of Jerico; W. A. Carender, cashier Farmers State Bank.

THE FARMERS BANK OF JERICO SPRINGS

Whatever the reason for the sale, some of the investors behind Farmers State Bank weren’t ready to give up. They joined with a newcomer to town, R. E. Porta, to raise $20,000 in capital and just more than a year later, on May 20, 1912, the group launched the similarly named Farmers Bank of Jerico Springs.

On May 24, The Optic reported, “The organization of the Farmers Bank of Jerico Springs has just been completed. This bank will be one of the strongest in the county, having for its stockholders about 20 representative citizens of this community. It will be backed by over $200,000 worth of real property.”

The editor took particular note of R.E. Porta, the new man in town who’d helped organize the bank.

“He comes to us very highly recommended from (Polk and St. Clair counties) where he has been in business for the past twenty-four years.” His most recent venture had been a bank in Osceola, which he had sold just before moving to Jerico

Mr. Porta was soon deeply entwined with his new home’s civic and fraternal clubs as well as its business affairs. He would be Jerico’s mayor in barely a decade. He also would bring disaster to the bank.

The Optic rounded out its coverage of the new bank with a list of stockholders:. E.D. Whitehorn Sr., W. L. Yates, B. L. Yeater, R. E. Porta, G.W. Freize, M. E. Taylor, Mrs. Nora Walker, S.H. Wilson, N. H. Mann, E.R Hightower, Molly H Gates, F. K. Crawford, J. D. Jones, J. R. Todd, F.D. Granger and Mrs. Hattie Sawyer.

The Optic said the officers were G.W. Freize, president, M. E. Taylor, vice president, and R. E. Porta, cashier, but the bank’s first annual report said the president was W. H. Umbarger, the vice president was R. H. Welty, the cashier was Mr. Porta and the assistant cashier was I. L. Arnold.

Whichever, at least five of the officials in the new bank – Mr. Freize, Mr. Taylor, Mr. Umbarger, Mrs. Gates and Mr. Arnold — had also been stockholders in the short-lived Farmers State Bank.

The group’s second try proved more successful in the end though after more than two years, as of Oct. 31, 1914, the bank had amassed just $30,000 in assets, while the Bank of Jerico held more than $90,000.

But trouble, the exact nature of which I do not know, hit the Bank of Jerico and it was “absorbed” by the Farmers Bank in June of 1916. The Bank of Jerico had lasted 15 years, the longest lived of Jerico’s banks.

The Optic did not report a reason for the closing, but in the June 6, 1916 issue, wrote extensively on a public meeting called in the “Springs park … to devise ways and means where the people who were interested in the Bank of Jerico, which closed Tuesday morning of last week (May 31), might consider the proposition offered by the Farmers Bank to take over the good assets of the Bank of Jerico and liquidate its indebtedness.”

A key part of the plan was to increase Farmers Bank’s capital from $10,000 to $20,000 through a new stock sale.

The Optic said that men and women gathered in groups “intensively” discussing the issues and that “the situation became tense” and “all approached the hour (of the meeting) with foreboding and dread.”

Someone suggested invoking divine guidance, which the Optic said resulted in Rev. Welsh making “the most direct, sublime and touching appeal” to God, after which he “touched every phase of our situation, bringing in harmony every discordant thought and preparing every heart and mind in his presence to think and act justly and rightly with his fellow man.”

The Optic continued, “At the close of the prayer a change had been wrought. People mingled and co-mingled and a spirit of toleration began to be manifested and in an incredibly short time petitions were being circulated among the farmers and business men to take stock in the Farmers Bank, … and before night there were 75 shares of stock raised among the farmers and business men, sufficient to institute the transfer (of the Bank of Jerico to Farmers Bank).

“The two institutions are now busy arranging matters and setting things in order for the change and in a few days the new bank will be ready for business if nothing comes up to block the negotiations.”

Nothing did, and Farmers Bank prospered over the coming 18 months, its assets growing from $103,000 in 1916 to $171,000 at the end of 1918.

THE PEOPLES BANK OF JERICO

Once again, though, Jerico’s competitive spirit, perhaps encouraged by the World War I-fueled prosperity of the moment, produced another bank in 1919.

“The People’s Bank of Jerico Springs opened its doors for business Tuesday morning July 8th in its building in the Gates Block,” the Optic reported in the July 11 issue.

“The building has been remodeled inside and out and new fixtures installed. The big safe arrived Tuesday and put in place in the north window in the bank. The new bank opens under very favorable conditions and they report their first day’s business show the deposit of $43,000.

“The bank’s officers and stockholders are among the best and most enterprising citizens of this part of the county and is among the strongest organizations in this part of the state and will be in position to take care of their customers at all times.”

Fred K. Harris was president, William Zollman was vice president, E. F. Peer was cashier and Raymond Johnson, assistant cashier. Additional board members were A.L. Brown, C. L. Long, J.R. Todd, J. D. Kifer, J. R. Beydler, C. F. Brasher, W. R. Hall, and F. D. Granger.

The Optic’s editor’s to-do list for the town included a rock road to a railroad point, a mill and elevator and a lumber yard.

The July 8, 1919 Optic

The Optic’s editor used the occasion to present a to-do list for the town.

“This gives Jerico Springs two good banks and what we need now is a rock road to some good railroad point and a good mill and elevator to give (farmers) a market for (grain) at home and save hauling their wheat away and then having to haul flour, bran and other feed back. A lumber yard would be a big help to Jerico Springs and vicinity.”

The reaction to the new bank could only have encouraged the optimists to see how all that could happen. After barely six weeks in business, on Aug. 28, 1919, Peoples Bank had amassed $74,715.18 in assets. Farmers Bank grew as well; it reported assets on that date of $203,25.07.

The combined assets of $277,390.25 ($4.04 million in 2019 dollars) was the most Jerico’s banks would ever hold, so far as I know.

Rosy as the moment may have seemed as the Roarin’ 20s began, all was not well in farm country.

In his 1921 report to the Missouri Legislature, Jewel Mays, secretary of the Missouri State Board of Agriculture, said, “farm products were in August of 1921 54% lower than one year ago and were 34% lower than the average of the past 10 years. Hogs, cattle, sheep, and chickens were in August 1921 34% lower than in 1920 and 17% lower than the 10-year average.”

Mr. Mays said such price crashes inevitably follow the end of a big war, and urged farmers to stick with the profession since the bottom was at hand.

He was wrong. Things would only get worse as the decade progressed.

“While many industries were thriving in the 1920’s, farm prices dropped due to huge agricultural surpluses, causing agricultural commodity prices and land values to drop steadily throughout the 1920’s,” said a recent report on 20th Century land values from the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service.

For Jerico and its banks, the looming trouble in the countryside would be aggravated by human failures and a fire.

A hint of difficulties ahead arrived in November,1923, when Farmers Bank began running weekly ads in the Optic, reassuring people of the bank’s soundness. The ads included the balance sheet, the names of the officers and directors as well as an estimate of their combined personal worth. Such ads were not particularly unusual, in a time when it didn’t take much more than a rumor to start a bank-killing run. In this case, however, the ads were harbingers of disaster and scandal.

On Christmas Day, 1923, Mr. Porta, Farmers Bank’s cashier since its founding in 1912, committed suicide as the state moved to take over the bank. Mr. Porta, 56, was also Jerico’s mayor.

Here’s the Optic’s report:

“The city of Jerico Springs and community were shocked Tuesday evening about 7 when the news flashed over town that R.E. Porta, cashier of the Farmers Bank of Jerico Springs had taken his own life by taking poison. The cause of this act was the closing of the Farmers Bank of this place.

“Mr. Porta was downtown Tuesday afternoon and seemed to be in his usual good spirits. When the mail arrived he went to the post office and got his mail and went home about 6:30. He told his wife he was going to the bank to put a notice on the door that the bank had closed its doors.

“But the supposition is that he never went to the bank as he was not gone long enough to make the trip. It is thought that he went to the well some distance from the house and got some water to take the strychnine and then went up the alley to the coal house where the bottle was found and stayed there until the medicine began to take effect and then came to the house and went upstairs and his wife followed him and noticed there was something wrong and asked him if he had taken anything and he nodded that he had.

“Dr. Prouse was summoned but before he arrived Mr. Porta had passed away. The coroner was summoned from El Dorado but upon arrival he found it was not necessary to hold an inquest as there was a type written letter found in his pocket to his family and among other things stated in that he was going to take his life.

“The bank inspector arrived here Thursday to take charge of the bank.”

The state bank examiner had possession of the Farmers Bank for a month, then appointed Jerico businessman F. M. Davis to be the bank’s receiver. “No statement has been given as to the condition of the bank at this time,” the Optic reported Feb. 1, 1924.

The same issue of the Optic contained a notice to bank creditors that they had until May 30 to get their claims on file.

As the receiver worked to wrap up the bank’s affairs, liquidate it and divide the proceeds among creditors and depositors , the state also oversaw negotiations aimed at salvaging whatever solvent assets Farmers Bank had left. The resulting plan had two elements, according to records from the Missouri Division of Finance: first, Farmers Bank would clear a chunk of bad debt from its books , and second, Farmers Bank would be sold to a newly created bank.

To accomplish the first goal, the bank’s board of directors signed a contract with the banks depositors (remember, board members were almost certainly depositors as well, probably major ones).

The depositors as a group agreed to pay face value for $18,525 in overdue notes held by the failed bank. That move apparently cleared the way for the sale of the bank, which resulted in creditors, including depositors, getting back 75 cents on the dollar, according to the state documents.

The second contract, for the sale of the insolvent Farmers Bank to the newly organized State Bank of Jerico, is remarkable in that the president and board of directors of the failed bank being sold is exactly the same as the president and board of directors of the new bank. James Nance signed the sales contract as president of both institutions.

Frank C. Millspaugh, Commissioner of Finance for the State Of Missouri, signed off on the arrangement and joined the banks in petitioning the circuit court to appove it. The court did so.

THE STATE BANK OF JERICO

The Optic said the State Bank of Jerico “was organized for the purpose of taking over the solvent assets of the Farmers Bank of Jerico Springs, which has been closed since December 26th, 1923.”

The paper continued “The stock in the new bank was sold at $160 per share and has all been paid up and the money is now in the custody of the following named stockholders of said bank who have been selected to serve as directors of the bank for the first year: James E. Nance, R.H. Welty, W. H. Umbarger , C.W.Cassell, Fred Albrecht and J.D. Jones. F.M. Davis cashier, Mrs. Meda Davis assistant cashier, James E Nance president.”

The new bank had sold $10,000 in capital stock.

The new bank’s officers and directors, all who had been officials of the failed bank, apparently emerged without blame for whatever problems brought it down. Mr. Porta apparently was alone in misdeeds.

The State Bank of Jerico opened for business Sept. 29, 1924. In its year-end report, it said it had assets of $60,246.96. That’s some 60 per cent less than the $147,456 its predecessor had claimed in April 1923.

The Peoples Bank reported assets of $76,507.59 that month, making the combined assets of Jerico’s banks $136,754.55, less than half the holdings of the town’s two banks in five years earlier.

Both banks were shrinking as the ‘20s limped along and the State Bank of Jerico was soon gone, destroyed by a fire that also claimed neighboring businesses. Full Optic fire story

Though the bank had insurance, its officers chose not to rebuild. Instead, they signaled an end to banking competition with this statement in the March 11 Optic:

“As you know we lost our banking house by fire and had no satisfactory place to do business and as we thought one good strong bank in Jerico would be better for all concerned than two, and the Peoples Bank made satisfactory terms with us, we have therefore consolidated and put our two banks together in one under the name of the Peoples Bank.

“Everyone who has shares in our bank will be issued an equal number in the new bank and all depositors can check on their accounts and make deposits there and we ask that all of our customers go ahead and do business with the consolidated institution which is still our bank.

“Thanking you for your support and asking the continuation of same with us in the new bank. We are your friends.”

Signed: James E Nance, F. M. Davis, C. P. Longacre, W. H. Umbarger, Fred Albrecht

The terms may have been “satisfactory” for the State Bank of Jerico, but they contained the seeds of disaster for Peoples Bank, which had increased its capital from $10,000 to $20,000 as part of the deal.

But it did not sell the stock, raising $10,000 in cash. Rather, it issued the stock based on its estimate of the net worth of the just acquired State Bank of Jerico, according to documents included in later court files.

Peoples Bank officials later asserted the arrangement was approved by state regulators. Division of Finance staffers said not; they also said Peoples Bank had over-estimated the net worth of the State Bank of Jerico, further worsening the bank’s “embarrassing position.”

The bank’s situation would have been near-untenable in the best of times, and the two years following the 1927 fire in Jerico were not the best of times.

Shortly after the merger, the Peoples Bank published a report on its condition as of April 12. It had $109,763.13 in assets, including about $78,000 in deposits. It had slightly more than $84,000 out in loans.

Those numbers dwindled downward along with the town’s fortunes, the assets falling to $93,000 when the bank closed on March 16, 1929.

The March 22 Optic said the board of directors closed it “following a slow run of several days.”

The Optic said, “The board sent a telegram to S. L. Cantley, state finance commissioner, to take charge of the institution. The bank had $20,000 capital and $4,000 surplus. Its last statements show deposits of $53,000 and loans of $64,000. W.T. Long was president and E. F. Peer cashier of the bank.”

BANKERS CHARGED

Cedar County Prosecuting Attorney O. O. Brown soon decided crimes had been committed in the week before the bank closed. Edd F. Peer, the cashier since the bank’s founding, was charged with receiving deposits into a bank knowing it to be in a failing condition.

A Cedar County Republican story about the case, reprinted in the Optic June 7, 1930, said “A good size the crowd was in town (Stockton) last Thursday to hear the preliminary hearing of Edd F.Peer, cashier of the defunct Peoples Bank of Jerico Springs on a charge of receiving deposits knowing the bank to be in a failing condition. The hearing was before G.W. Elliston Justice of the Peace.

“The evidence offered in the case tended to show that the bank had accepted at least two deposits within a few days preceding the closing of the bank on March 16th. The state was represented by O. O. Brown and Collins & Osbourne, and sought to prove that Mrs. Cantrell had made a time deposit to her checking account just previous to the closing of the institution.

“There was also some testimony that some of the directors and Mr. Peer had withdrawn their deposits a short time before the closing. Neale & Neuman appeared in defense of Mr. Peer.

“Judge Elliston decided the evidence was sufficient to bind the defendant over on both charges and the cases will be set for the November term of the circuit court in Stockton.”

But Prosecuting Attorney Brown wasn’t done. On Aug. 9th, the Optic reported that Mr. Brown “ordered the arrest of five officers of the defunct Peoples Bank of Jerico Springs last Monday.” In addition to Mr. Peer, those arrested were W. T. Long, J. W. Farmer, C. F Brasher and J. A. Brown.

“ Mr. Long, who is a director and the president to the closed institution, was charged with assenting to the acceptance of deposits while knowing the bank to be in a failing condition. Three charges of this nature were lodged against him,” the Optic reported. Mr. Farmer, Mr. Brasher and Mr. Brown, directors, were also arrested on the same three charges.

On Oct. 18, 1929, the Optic ran a piece from the Cedar County Republican in Stockton reporting preliminary hearings had been held in circuit court in the bank case, and that the five men had been bound over for trial. The cases were scheduled for the November court term.

Delays were encountered while the bankers sought a change of venue from Cedar County. On Jan. 24, 1930, the Optic reprinted a Nevada Mail story saying the Jerico bank case had been transferred from Cedar County to Vernon County.

Mr. Peer went on trial first and got a hung jury, but was convicted in a second trial. He was sentenced to two years in prison, and appealed the conviction to the Missouri Supreme Court.

On. Nov. 17, 1930, Mr. Long, the president, was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison. He, too, appealed to the Supreme Court, according to Vernon County court records.

“The high court’s ruling in the Peer case came first, on June 5, 1931. The conviction was unanimously reversed and a new trial ordered.”

The high court’s ruling in the Peer case came first, on June 5, 1931. The conviction was unanimously reversed and a new trial ordered.

In the end, Mr. Peer, who had faced five charges, had been convicted of but one offense – accepting a $61.50 deposit on March 9, a week before the bank closed on March 16. Among other defenses, Mr. Peer said he did not believe the bank to be failing of March 9, and contended there was no proof the bank was failing .

The Supreme Court agreed, saying the Vernon County trial judge had erred twice in permitting testimony and evidence on that point.

Once was in allowing the testimony of Frank M. Davis, a Jerico businessman appointed by the state as receiver of the closed bank, who estimated the value of the bank’s assets on March 9 at $40,000 less than the balance sheet showed. “We think the qualification of witness Davis to testify as he did to the value and solvency of the bank’s assets was not sufficiently shown,” the court said in its opinion.

The second error by the Vernon County judge was in allowing into evidence a letter sent to the Farmers Bank’s officers Feb. 28 by a deputy state bank commissioner, in which he outlined the bank’s “embarrassing condition” and reiterates points made with the bankers during a face-to-face meeting in Springfield earlier in the month, including the need for them to come up with $10,000 to save the bank.

The court agreed with Mr. Peer’s contention that the letter was not an official communication, and was therefore inadmissible hearsay. “It is plain that the letter contained statements and implications damaging to defendant, and we think it was clearly incompetent as hearsay,” the court’s opinion said.

“It was not the official report of the examiner. It did not purport even to be based thereon, but rather upon occurrences and the discussion at the Springfield conference and other matters and conditions which may or may not have been referred to in the examiner’s official report. Its admission was prejudicial error.”

The opinion in the Long case was issued in December. Like Mr. Peer, he had been in the end convicted of but one offense, this one involving a $200 deposit accepted on March 13, three days before the bank closed. Like Mr. Peer, he argued at his trial that he had not known and did not believe the bank to be in a failing condition. He had deposited money in it the day it closed, he said.

The witnesses in both trials had been largely the same and in a decision that quoted extensively from the Peer ruling, the court overturned Mr. Long’s conviction and ordered a new trial. The issues were the same – the trial court should have allowed neither the testimony of Frank Davis about the value of the bank’s assets nor the admission into evidence of the letter regarding the Springfield meeting.

The Supreme Court rulings brought the criminal cases to a close. In May, 1932, T. B. Hembree, who had replaced O. O. Brown as Cedar County Prosecuting Attorney, filed notices he would not further prosecute Mr. Long, Mr. Peer or J. W. Farmer, a director whose trial had ended in a hung jury. (I’m assuming charges against directors C. F Brasher and J. A. Brown were also dropped though I haven’t seen the paperwork.)

Another two years would pass before the bank’s business affairs were settled.

The order of final settlement and distribution was filed June 3,1935, according to Division of Finance records. It provided that all Peoples Bank creditors would be paid at 66 cents on the dollar.

`THE GRAND FINALE’

A small group of people gathered on a chill November afternoon in 1936 at the still vacant lot where Jerico State Bank had stood before the fire 9 years earlier.

The chatter of an auctioneer soon filled the air as he put the former bank’s remaining property – a few office chairs, safes, typewriter and desk and the corner lot where the bank building stood -on the block.

The lot brought $50. The time lock safe brought $20. The Optic said the sale of the smaller items brought the total to approximately $125 .

The Optic report concluded, “So the grand finale of the banking business in Jerico Springs has been brought to a end.”

EPILOGUE

Jerico never recovered from the blows of the ’20s. Retailers continued to fail and as its advertisers went out of business, so did the Optic, which went under in February of 1937. The disappearing retailers and improving roads combined to give people fewer reasons to go to Jerico just as it got easier to go elsewhere.

The population dipped to 179 in 1960 but has since recovered somewhat and stood at 230 in a 2016 Census estimate. The streets are still unpaved, except for the two state blacktops that intersect in town. The springs still run, though more slowly it seems to me. The annual Founders Day Picnic is on life support.

Retail is gone. As of this writing (March 2019) There is no place to buy a jug of milk or gas up your car. You can’t even find an ATM.

Copyright 2019 John Beydler

Who knew small-town banking could be so competitive?

LikeLike

It was very interesting as I have a degree in History it was well written and very informative. My father owned several of the building on the south side and several houses and trailers during the late 70, and 80,s and then my mother owned the postoffice until recent years she is soon to be 97. So I found out a lot of history and thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

Thank you for this.Very informative.Would like more history of just the town in general and the fire.Thank you.

LikeLike

Small

LikeLike

sexy

LikeLike

white

LikeLike